The one-armed woman said, “There was a movie called Maple recently. I don’t know if you’ve seen it. At the end, an adult and a child stand in front of the grave of a Red Guard who had died during the faction civil wars. The child asks the adult, ‘Are they heroes?’ The adult says no. The child asks, ‘Are they enemies?’ The adult again says no. The child asks, ‘Then who are they?’ The adult says, ‘History.’”

– Ch 26, No One Repents

INTERROGATOR: Then why do you have such hope for it, thinking that it can reform and perfect human society?

YE: If they can cross the distance between the stars to come to our world, their science must have developed to a very advanced stage. A society with such advanced science must also have more advanced moral standards.

– Ch 31, Operation Guzheng

Netflix has released its international version of Liu Cixin’s novel The Three Body Problem, a year after China’s own TV adaptation. It has attracted polarizing evaluations – many audiences believe it made the world small and petty by focusing on the group of young scientists who all know each other, while others praise it for an intelligent series that seeks to tackle science and society. Audiences in China generally panned the series for making the present-day story set entirely in the UK, and nationalists opposed the scenes showing the violence of the Cultural Revolution. The Chinese TV version doesn’t include the Cultural Revolution scenes, most likely because of censorship.

As a Chinese person who grew up mostly in North America and who has gone back to China to work on two occasions, I observe that neither global audience perspective nor Chinese nationalist critiques really get at the heart of what the Netflix version changed and its implications for understanding China. Netflix’s 3 Body is very well-researched, quite faithful to the novel’s depiction of the past and to Liu Cixin’s conceptualization of the story. However, by truncating the story and internationalizing it, the Netflix version unwittingly created a simplistic picture of China, and fails to capture some of the nuanced worldviews in the novel. By setting the present day story outside China, it also limits the legacy of the Cultural Revolution to the actions of one woman, and fails to represent the novel’s themes of science, history, and morality in China.

In the spirit of threes, this post will outline some general facts of history and society which the Netflix series didn’t have time to include or changed due to storytelling purposes, a second post will address how the Netflix version misses out on a particular Chinese worldview and Chinese representation, and the third post will delve into the intertwined themes of science, history, and morality in the novel. Obviously, these posts assume you’ve read the novel or watched the Netflix series, so spoilers abound.

Part I. Netflix’s changes and resulting omissions / misunderstandings of Chinese history

Points 1-3 discuss minor details which were left out or changed so as to streamline the story, and therefore I’m not criticizing Netflix, just pointing out missing details that could help audiences understand some social and historical context. Point 4 and 5 are more serious, as they lead to a misimpression that power in China is always completely centrally controlled and that discussions of the Cultural Revolution are suppressed.

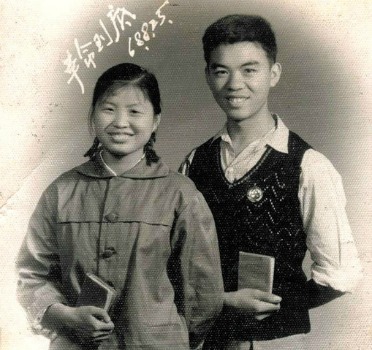

1) The contemporary setting conflicts with how old Ye Wenjie should be. Ye Wenjie has a birthday of 1943 (ch 25). This places her as in in her late twenties and thirties during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1977). The Three Body Problem novel was written in the 2000s and the story is meant to be set then. Around this time she would have been in her early 60s. China’s official retirement age is lower than in the west: for men it is 60, and for women it is 55 (though a lot of academics work some years beyond this, since their particular skillsets are not easily replaceable). Ye’s age in the novel allows her to be elderly and retired, but still young enough to be a commander of the ETO. The setting of Netflix’s version is probably meant to be contemporary to its release date, which makes Ye in her 80s. To make her in her 60s by the 2020s would mean she couldn’t have been impacted by the Cultural Revolution in the same way. My parents were born in 1956, and some of my grandparents were arrested and weren’t home a lot, but my parents were too young to participate in factional fighting (see #4) or be directly punished for reactionary ideologies.

2) Ye and Evans could not have met in 1977. The Netflix version probably didn’t want to jump around between too many different years in Ye’s past, and also wanted Ye and Evans to have a daughter, so set the meeting between them in 1977 (ep 2). While this was the end of the Cultural Revolution, meeting a foreigner at the time was highly improbable and would immediately register as such for Chinese audiences. In the book, Ye and Evans met much later, in the 1980s. Chapter 18 states, “The mother and daughter only left Radar Peak in the mid-eighties, when Red Coast Base was finally decommissioned. Ye later returned to Tsinghua, her alma mater, to teach astrophysics until retirement.” It was half a year after her return to Tsinghua that she was given the task of scouting out a new location for a radio astronomy observatory (opening of ch 27).

Roughly, the end of the Cultural Revolution goes: Mao and Zhou Enlai both died in 1976. If Zhou had lived longer, maybe he could have taken over. Instead, power went to Hua Guofeng. In response, Mao’s wife Jiang Qing and 3 others formed the “Gang of Four” to continue the political struggle in Mao’s name. Hua vehemently opposed them, opposed the continuation of the Cultural Revolution, and removed them from power before the end of 1976. Deng Xiaoping was part of Hua’s government, and ousted Hua in 1978 to take China in a more liberalized direction. Through all of this chaos, it is unlikely Ye and her team would have gotten resources to set up a new observatory, and it is implausible that a random American whose family built an oil empire could waltz into China and hang around to save birds. The US and China didn’t even establish official diplomatic relations til 1979, so no visas were handed out going back and forth between these countries.

3) Communist revolutionary ideology discouraged romance, and pursing romance for Ye would have been a huge political risk. The Netflix series tries to humanize Ye Wenjie by inventing a romantic attachment between her and Bai Mulin, the bespectacled journalist she meets at the logging camp (ep 2), and then a passionate fling with Mike Evans. Like Evans showing up in China in 1977, the scene where Ye and Bai are intimate in a small tent would also strike Chinese audiences as unlikely. The novel shows that Ye, who is politically suspect, never really relaxes until the end of the Cultural Revolution (opening of ch 23). It also states, “In peace, what had been suppressed by anxiety and fear began to reawaken. Ye found that the real pain had just begun.” Essentially, she was completely dissociated and numb from her trauma, and couldn’t even feel pain; it is unlikely she had the emotional capacity to think about love.

In addition, the ideology until the late 1970s was that feelings and personal relationships are bourgeoisie and unworthy of attention, sex and gender difference were never discussed, and this kind of repression basically led to people actually not feeling attraction and romance. There was a story going around that a young revolutionary couple who got married went to see the doctor because the woman couldn’t get pregnant, and the doctor finds out that they have just been getting into bed and hugging. This is probably not true, but it’s told as a joke that reveals how human responses were impacted during this time.

This repression was especially strong for women because they were seen as more domestic and emotional to begin with (for an accessible academic analysis of this, see Mayfair Yang’s research on gender erasure in China). Because romance and feelings were politically suspect, Ye venturing a romantic relationship with Bai would be a huge political risk; if she were found out, she would have been branded as a reactionary trying to use counter-revolutionary feminine wiles to seduce a comrade. The novel repeatedly states that Ye became extremely sensitive to political implications of her actions and the words she used, so she would not have acted on attraction, even if she felt any in the first place.

4) The cultural revolution is portrayed as centrally planned and directed, which was not really the case. The most significant event that impacted Ye Wenjie was the struggle session where Red Guards killed her father, so only that violence was in Netflix’s series. If someone who knew nothing about this period watched this opening scene of episode 1, they would probably come away thinking that all the guards are commanded by the CCP’s central leadership, and they operated like a unified police force based on centrally devised political rules.

The novel actually does not open with this, but instead with the fighting between two factions of Red Guards where a young woman tries to charge the other faction and is repeatedly shot. It’s easy to think of China as a society where the national government meticulously controls all aspects of society and that there is a single dominant ideology, but this is not true now and was also not entirely true then. The Cultural Revolution was indeed started by Mao, and he supported the Red Guards’ violent activities. He told the country that other leaders had abandoned revolutionary ideals and need to be overthrown as a way of getting rid of his political opponents. However, different factions of Red Guards all had their own interpretations of Mao’s ideologies, fought each other, and sometimes used Mao as a cover to pursue grievances. This is not an apologia for China’s leadership, but a) thinking that the central government can control everything is giving them too much credit, and b) it is way more sinister and controlling to sit back and set your people against each other, so you can keep your hands nominally clean and your people are too distracted to overthrow you. When the Gang of Four was struck down, the Cultural Revolution was initially blamed on them. Currently, China’s leadership fans nationalism for the same purpose. I will return to this more when discussing the complex morality the novel tries to express.

5) Interviews with Rosalind Chao imply that the Cultural Revolution is never discussed in China, which is not true. This is not Netflix’s responsibility, but should be addressed here before I get into the more analytical posts. MovieWeb has an article on the backlash from Chinese audiences, where they describe how the Cultural Revolution scenes were not received well. They ask Chao, who plays older Ye Wenjie, about the issue: “For actress Rosalind Chao, who plays the adult version of Ye Wenjie in the series, the importance of an adaptation made internationally is huge when depicting parts of history that some would prefer to be forgotten.” Among other responses, Chao says, “They don’t talk about the Revolution. It’s so ingrained not to discuss it, whereas it’s a huge part of history.” Chao is descended from Mainland Chinese parents and speaks Chinese, and has had distant family impacted by the Cultural Revolution. In a Variety interview, she says, “A lot of my family remained in China after my parents left. There are no remnants of the past. No photos of my mother. But nobody talks about it. If you ask somebody about it, they really don’t want to. It’s very Chinese to say if something bad happens, okay, it’s over now. That’s kind of the way I was raised. There’s a cover on the emotions from people of that period. And Ye is like that.”

What Chao is saying is that people in China don’t really want to talk about their horrible past, and what someone might mistakenly take from her statements is that the government does not let people talk about it. Neither is really true. Different eras of Chinese government have had different approaches to how to talk about the Cultural Revolution. Immediately after liberalization in the late 1970s-1980s, there was a whole genre called “scar literature” written by people who wished to express their suffering, for example. Even a few years ago, China’s leadership outright condemned the Cultural Revolution and outright stated that Mao was responsible. I don’t have a source for this, but as a Chinese person picking up stuff by osmosis, it seems like the current regime could do this because they view themselves as having China from Mao’s dotage and returning the country to the right path. This discussion in the /threebody subreddit also gives an indication that it’s really not uncommon to condemn the Cultural Revolution in China, and a lot of non-Chinese don’t know this (the post is by someone who was surprised that it was in the novel).